Despite the fact that increasing numbers of San Franciscans are making the choice to live without private vehicles, the number of cars in San Francisco continues to increase.

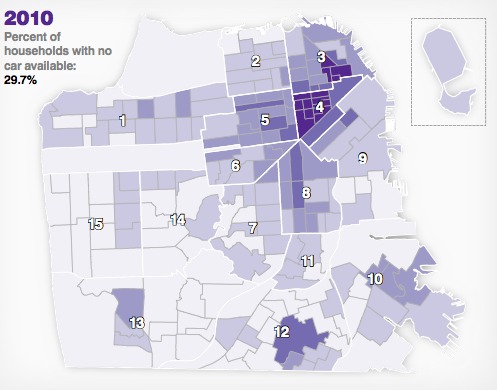

Of the 346,842 occupied housing units in the city, 31.4%, or about 108,908, don’t have access to privately-owned cars, trucks, or other motor vehicles, according to U.S. Census data. The 1.9 percent increase — or 6,589 housing units without access to vehicles — marks an ongoing trend, in one of the most dense cities in the United States.

Of the 346,842 occupied housing units in the city, 31.4%, or about 108,908, don’t have access to privately-owned cars, trucks, or other motor vehicles, according to U.S. Census data. The 1.9 percent increase — or 6,589 housing units without access to vehicles — marks an ongoing trend, in one of the most dense cities in the United States.

But since 2008 there has also been a 1.5 percent increase in the number of cars registered in San Francisco, according to the California Department of Motor Vehicles. That’s 5,544 more cars, for a total of 385,442 registered to San Francisco addresses.

And there are likely more cars owned and operated by San Franciscans than DMV data suggests. The Appeal has spied numerous vehicles with out of state plates in the city, some parked for long periods of time in the same neighborhood.

But specific data on those vehicles — likely scofflaws, as the DMV requires such vehicles to be registered within 20 days (Military personnel and their families stationed in California are exempt from the requirement) — is hard to come by.

Neither the DMV nor the California Highway Patrol tracks the number of scofflaws, but CHP does have an website where such people can be reported.

Although it’s possible to obtain exemptions, if caught many would face a fine — and have to pay registration fees in California. One of the most common reason for evading vehicle registration requirements in California is evading payments of registration fees and taxes, according to Artemio Armenta of the DMV. Others include being unaware of the law, and unable to pass the smog test.

Increasing numbers of cars don’t necessarily translate to more commuters on the road, at least in San Francisco. Data from last year indicates that a three percent drop in commuters choosing to drive alone, for a total of about 37.5 percent, said SFMTA spokesperson Paul Rose. Planning Department documents indicate that between 2000 and 2010 there’s been a 10 percent drop in workers who commute via car, truck or van — dropping from 51.3 to 41.7 percent.

Most of the workers who commute by car live outside the downtown core of the city, in outlying districts like the Richmond, Ingleside, Sunset and Portola. The heaviest concentration of vehicle commuters is in Seacliff — with over 80 percent commuting to work with a vehicle, according to Planning Department documents.

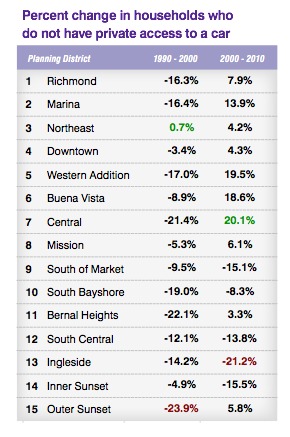

The majority of households without access to a car are concentrated in the northeastern part of the city, according to the Planning Department. But even in areas where car ownership is uncommon, pockets of car owners remain — such as the northern tip of district two.

The are two main reasons for the relatively high car-less rate in the city, according to Urban Geography professor Jason Henderson. First, many lower income households don’t have access to vehicles — cars, trucks, or motorcycles — at all, Henderson said. District 10, which contains the Bayview, is one such area, according to Planning Department documents. The second factor, according to Henderson, is that many city residents that have the means to own a car have decided not to own one.

Henderson is especially interested in that second group of people because it’s a newer trend, and it’s apparently by choice — not a reflection of the increasingly hostile rental and real estate market that has created an ongoing economic hardship for low and middle income residents.

Young people are also often deferring car ownership because alternative modes of transportation — car share, Muni, cycling — are (relatively speaking) pretty good in San Francisco, said Teresa Ojeda, Senior Planner, Information and Analysis at the Planning Department.

Although her department hasn’t studied the phenomenon extensively, officials are aware of the potential impacts on transportation planning now and in the future.

Even of the occupied housing units with access to a single vehicle, many of those are likely situations with multiple occupants. “When you’re talking about San Francisco, you very well may be talking about three roommates,” Henderson said.

Building design contributes too. Households that have a limited amount of parking are less likely to, for example, buy a car for a child, Ojeda said. In certain districts — and many of the upcoming developments — developers are building little to no new parking. The thinking at the Planning Department is that people who can’t find parking often don’t buy cars, Ojeda said. In many districts street parking is capped or being removed.

The city’s density also likely contributes to the high carless rate. People are able to get to work, run errands and engage in leisure activities often without needing to use a vehicle, Henderson said.

One reason may be access to alternative forms of transportation. The Department of Public Works tries to identify corridors and streets people use to get to parks, and those streets where pedestrian and bicycle improvements would encourage more people to use them. The goal is to figure out ideal and common routes people on foot and on bikes use to get from one place to another.

But, such improvements can be controversial — especially because many eliminate parking spaces.

About half of the city’s residents get around the city on foot, Muni, and bicycles, according to Rose. In a written statement, Rose said that given the current job growth and housing changes that are anticipated by officials, the city cannot rely car oriented transportation to support “our economic way of life.”